In June, I wrote the article below for The Conversation. Today I start teaching my Fall 2020 (online) course on the foundations, histories, myths, and futures surrounding learning technologies, and I thought it was a good time to republish this piece here under its original Creative Commons license as a reminder for myself and others. The original article is here.

The 7 elements of a good online course

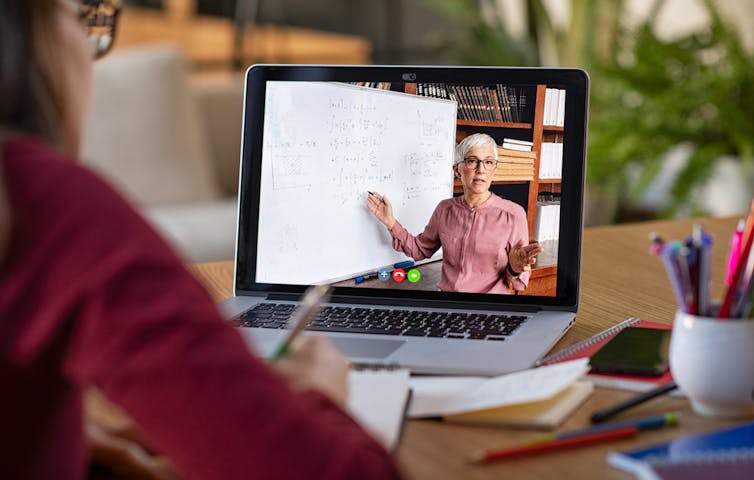

With very few exceptions, online teaching and learning will be the primary mode of education for the majority of higher education students in many jurisdictions this fall as concerns about COVID-19 extend into the new school year.

As an education researcher who has been studying online education and a professor who has been teaching in both face-to-face and online environments for more than a decade, I am often asked whether online learning at universities and colleges can ever be as effective as face-to-face learning.

To be clear: this isn’t a new question or a new debate. I’ve been asked this question in various forms since the mid-2000s and researchers have been exploring this topic since at least the 1950s.

The answer isn’t as unequivocal as some would like it to be. Individual cherry-picked studies can support any result. But systematic analyses of the evidence generally show there are no significant differences in students’ academic outcomes between online and face-to-face education.

Researchers also find that some students perform worse online than others — and that some of those differences can be explained by socioeconomic inequities.

Advice for students and parents

The problems with media comparison studies — that is, those that compare outcomes between one medium, such as face-to-face, to another medium, such as online — are such that many researchers advocate against them. How can students who enrol in online courses in the fall know they are receiving a good educational experience? What are some of the qualities of a good online course?

Here’s some advice for students (and their parents) about what to look for as learning remains online.

- A good online course is informed by issues of equity and justice. It takes into account social, political and cultural issues — including students’ backgrounds and socioeconomic circumstances — to craft a learning experience that is just. This may take many forms. In practice, it may mean a diverse and intersectional reading list. It means audiovisual materials that don’t stereotype, shame or degrade people. It may mean that open educational resources are prioritized over expensive textbooks.

- A good online course is interactive. Courses are much more than placeholders for students to access information. A good online course provides information such as readings or lecture videos, but also involves interactions between professor and students and between students and students. Interactions between professor and students may involve students receiving personalized feedback, support and guidance. Interactions among students may include such things as debating various issues or collaborating with peers to solve a problem. A good online course often becomes a social learning environment and provides opportunities for the development of a vibrant learning community.

- A good online course is engaging and challenging. It invites students to participate, motivates them to contribute and captures their interest and attention. It capitalizes on the joy of learning and challenges students to enhance their skills, abilities and knowledge. A good online course is cognitively challenging.

- A good online course involves practice. Good courses involve students in “doing” — not just watching and reading — “doing again” and in applying what they learned. In a creative writing class, students may write a short story, receive feedback, revise it and then write a different story. In a computer programming class, they may write a block of code, test it and then use it in a larger program that they wrote. In an econometrics class, they might examine relationships between different variables, explain the meaning of their findings and then be asked to apply those methods in novel situations.

- A good online course is effective. Such a course identifies the skills, abilities and knowledge that students will gain by the end of it, provides activities developed to acquire them and assesses whether students were successful.

- A good online course includes an instructor who is visible and active, and who exhibits care, empathy and trust for students. This individual understands that their students may have a life beyond their course. Not only do many students take other courses, but they may be primary caretakers, have a job or be struggling to make ends meet. Good online courses often include instructors who are approachable and responsive, and who work with students to address problems and concerns as they arise.

- A good online course promotes student agency. It gives students autonomy to enable opportunities for relevant and meaningful learning. Such a course redistributes power – to the extent that is possible – in the classroom. Again, this may take many forms in the online classroom. In the culinary arts, it may mean making baking choices relevant to students’ professional aspirations. In an accounting course, students could analyze the financial statements of a company they’re interested in rather than one selected by the instructor. Such flexibility not only accommodates students’ backgrounds and interests, it provides space for students to make the course their own. In some cases it might even mean that you – the student – co-designs the course with your instructor. This is the kind of flexibility higher education systems need.

These qualities aren’t qualities of good online courses. They are qualities of good courses, period.

Physical proximity isn’t a precondition for good education. Comparing one form of education to another distracts us from the fact that all forms of education can — and should — be made better.